Test-driven development (TDD) (Test Driven Development: By Example 1st Edition Beck 2003; Test Driven Development: A Practical Guide (Coad) 1st Edition Astels 2003), is an evolutionary approach to development which combines test-first development where you write a test before you write just enough production code to fulfill that test and refactoring.

Goal of TDD

One view is the goal of TDD is specification and not validation (Agile Software Development, Principles, Patterns, and Practices 1st Edition Martin, Newkirk, and Kess 2003). In other words, it’s one way to think through your requirements or design before your write your functional code (implying that TDD is both an importan agile requirements and agile design technique). Another view is that TDD is a programming technique. As Ron Jeffries likes to say, the goal of TDD is to write clean code that works. I think that there is merit in both arguments, although I lean towards the specification view, but I leave it for you to decide.

1. What is TDD?

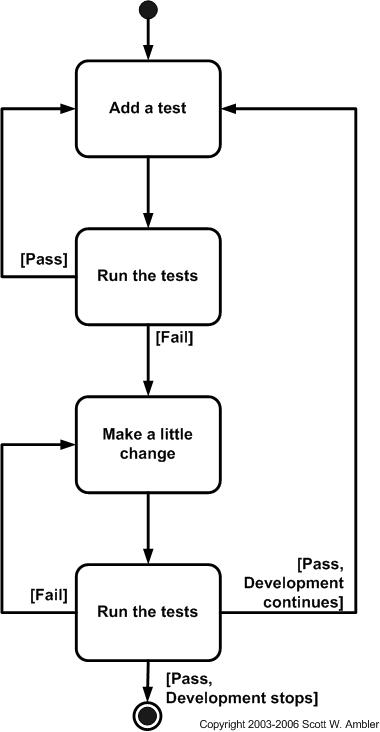

The steps of test first development (TFD) are overviewed in the UML activity diagram of Figure 1. The first step is to quickly add a test, basically just enough code to fail. Next you run your tests, often the complete test suite although for sake of speed you may decide to run only a subset, to ensure that the new test does in fact fail. You then update your functional code to make it pass the new tests. The fourth step is to run your tests again. If they fail you need to update your functional code and retest. Once the tests pass the next step is to start over (you may first need to refactor any duplication out of your design as needed, turning TFD into TDD).

Figure 1. The Steps of test-first development (TFD).

TDD simple formula:

TDD = Refactoring + TFD.

TDD completely turns traditional development around. When you first go to implement a new feature, the first question that you ask is whether the existing design is the best design possible that enables you to implement that functionality. If so, you proceed via a TFD approach. If not, you refactor it locally to change the portion of the design affected by the new feature, enabling you to add that feature as easy as possible. As a result you will always be improving the quality of your design, thereby making it easier to work with in the future.

Instead of writing functional code first and then your testing code as an afterthought, if you write it at all, you instead write your test code before your functional code. Furthermore, you do so in very small steps – one test and a small bit of corresponding functional code at a time. A programmer taking a TDD approach refuses to write a new function until there is first a test that fails because that function isn’t present. In fact, they refuse to add even a single line of code until a test exists for it. Once the test is in place they then do the work required to ensure that

the test suite now passes (your new code may break several existing tests as well as the new one). This sounds simple in principle, but when you are first learning to take a TDD approach it proves require great discipline because it is easy to “slip” and write functional code without first writing a new test. One of the advantages of pair programming is that your pair helps you to stay on track.

There are two levels of TDD:

- Acceptance TDD (ATDD).

With ATDD you write a single acceptance test, or behavioral specification depending on your preferred terminology, and then just enough production functionality/code to fulfill that test. The goal of ATDD is to specify detailed, executable requirements for your solution on a just in time (JIT) basis. ATDD is also called Behavior Driven Development (BDD).

- Developer TDD.

With developer TDD you write a single developer test, sometimes inaccurately referred to as a unit test, and then just enough production code to fulfill that test. The goal of developer TDD is to specify a detailed, executable design for your solution on a JIT basis. Developer TDD is often simply called TDD.

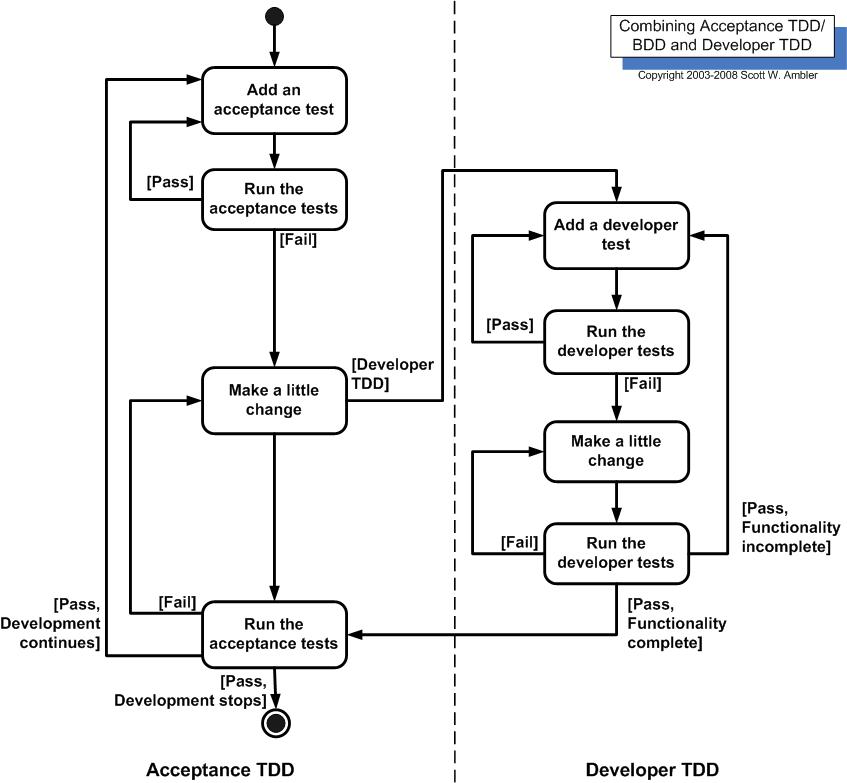

Figure 2 depicts a UML activity diagram showing how ATDD and developer TDD fit together. Ideally, you’ll write a single acceptance test, then to implement the production code required to fulfill that test you’ll take a developer TDD approach. This in turn requires you to iterate several times through the write a test, write production code, get it working cycle at the developer TDD level.

Figure 2. How acceptance TDD and developer TDD work together.

Note that Figure 2 assumes that you’re doing both, although it is possible to do either one without the other. In fact, some teams will do developer TDD without doing ATDD, see survey results below, although if you’re doing ATDD then it’s pretty much certain you’re also doing developer TDD. The challenge is that both forms of TDD require practitioners to have technical testing skills, skills that many requirement professionals often don’t have (yet another reason whygeneralizing specialists are preferable to specialists).

An underlying assumption of TDD is that you have a testing framework available to you. For acceptance TDD people will use tools such as Fitnesse or RSpec and for developer TDD agile software developers often use the xUnit family of open source tools, such as JUnit or VBUnit, although commercial tools are also viable options. Without such tools TDD is virtually impossible.

Figure 3 presents a UML state chart diagram for how people typically work with such tools. This diagram was suggested to me by Keith Ray.

Figure 3. Testing via the xUnit Framework.

Kent Beck, who popularized TDD in eXtreme Programming (XP) (Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change US Ed Edition Beck 2000), defines two simple rules for TDD (Test Driven Development: By Example 1st Edition Beck 2003).

First, you should write new business code only when an automated test has failed. Second, you should eliminate any duplication that you find. Beck explains how these two simple rules generate complex individual and group behavior:

- You develop organically, with the running code providing feedback between decisions.

- You write your own tests because you can’t wait 20 times per day for someone else to write them for you.

- Your development environment must provide rapid response to small changes (e.g you need a fast compiler and regression test suite).

- Your designs must consist of highly cohesive, loosely coupled components (e.g. your design is highly normalized) to make testing easier (this also makes evolution and maintenance of your system easier too).

For developers, the implication is that they need to learn how to write effective unit tests. Beck’s experience is that good unit tests:

- Run fast (they have short setups, run times, and break downs).

- Run in isolation (you should be able to reorder them).

- Use data that makes them easy to read and to understand.

- Use real data (e.g. copies of production data) when they need to.

- Represent one step towards your overall goal.

2. TDD and Traditional Testing

TDD is primarily a specification technique with a side effect of ensuring that your source code is thoroughly tested at a confirmatory level. However, there is more to testing than this. Particularly at scale you’ll still need to consider other agile testing techniques such as pre-production integration testing and investigative testing. Much of this testing can also be done early in your project if you choose to do so (and you should).With traditional testing a successful test finds one or more defects. It is the same with TDD; when a test fails you have made progress because you now know that you need to resolve the problem. More importantly, you have a clear measure of success when the test no longer fails. TDD increases your confidence that your system actually meets the requirements defined for it, that your system actually works and therefore you can proceed with confidence.

As with traditional testing, the greater the risk profile of the system the more thorough your tests need to be. With both traditional testing and TDD you aren’t striving for perfection, instead you are testing to the importance of the system. To paraphrase Agile Modeling (AM), you should “test with a purpose” and know why you are testing something and to what level it needs to be tested. An interesting side effect of TDD is that you achieve 100% coverage test – every single line of code is tested – something that traditional testing doesn’t guarantee (although it does recommend it). In general I think it’s fairly safe to say that although TDD is a specification technique, a valuable side effect is that it results in significantly better code testing than do traditional techniques.

If it’s worth building, it’sworth testing. If it’s not worth testing, why are you wasting your time working on it?

3. TDD and Documentation

Like it or not most programmers don’t read the written documentation for a system, instead they prefer to work with the code. And there’s nothing wrong with this. When trying to understand a class or operation most programmers will first look for sample code that already invokes it. Well-written unit tests do exactly this – the provide a working specification of your functional code – and as a result unit tests effectively become a significant portion of your technical documentation. The implication is that the expectations of the pro-documentation crowd need to reflect this reality.

Similarly, acceptance tests can form an important part of your requirements documentation. This makes a lot of sense when you stop and think about it. Your acceptance tests refine exactly what your stakeholders expect of your system, therefore they specify your critical requirements. Your regression test suite, particularly with a test-first approach, effectively becomes detailed executable specifications.

Are tests sufficient documentation? Very likely not, but they do form an important part of it. For example, you are likely to find that you still need user, system overview, operations, and support documentation. You may even find that you require summary documentation overviewing the business process that your system supports. When you approach documentation with an open mind, I suspect that you will find that these two types of tests cover the majority of your documentation needs for developers and business stakeholders. Furthermore, they are a wonderful example of AM’s Single Source Information practice and an important part of your overall efforts to remain as agile as possible regarding documentation.

4. Test-Driven Database Development

At

the time of this writing an important question being asked within the agile

community is “can TDD work for data-oriented development?” When you look at the process depicted in Figure

1 it is important to note that none of the steps specify object programming

languages, such as Java or C#, even though those are the environments TDD is

typically used in. Why couldn’t you

write a test before making a change to your database schema?

Why couldn’t you make the change, run the tests, and refactor your schema

as required? It seems to me that

you only need to choose to work this way.

My

guess is that in the near term database TDD, or perhaps Test Driven Database

Design (TDDD), won’t work as smoothly as

application TDD. The first

challenge is tool support. Although

unit-testing tools, such as DBUnit, are

now available they are still an emerging technology at the time of this writing.

Some

DBAs are improving the quality of the testing they doing, but I haven’t yet

seen anyone take a TDD approach to database development. One challenge is that unit testing tools are still not well accepted within the data

community, although that is changing, so my expectation is that over the next

few years database TDD will grow. Second,

the concept of

evolutionary development is new to many data professionals and as

a result the motivation to take a TDD approach has yet to take hold.

This issue affects the nature of the tools available to data

professionals – because a

serial mindset still dominates within the

traditional data community most tools do not support evolutionary development.

My hope is that tool vendors will catch on to this shift in paradigm, but

my expectation is that we’ll need to develop open source tools instead.

Third, my experience is that most people who do data-oriented work seem

to prefer a model-driven, and not a test-driven approach.

One cause of this is likely because a test-driven approach hasn’t been

widely considered until now, another reason might be that many data

professionals are likely visual thinkers and therefore prefer a modeling-driven

approach.

5. Scaling TDD via Agile Model-Driven Development (AMDD)

TDD is very good at detailed specification and validation,

but not so good at thinking through bigger issues such as the overall design,

how people will use the system, or the UI design (for example). Modeling,

or more to the point agile model-driven

development (AMDD) (the lifecycle for which is captured in

Figure 4) is better

suited for this. AMDD addresses the

agile scaling issues that TDD does not.

Figure 4. The Agile Model Driven

Development (AMDD) lifecycle.

Comparing TDD and AMDD:

- TDD shortens the programming feedback loop whereas AMDD

shortens the modeling feedback loop. - TDD provides detailed specification (tests) whereas

AMDD is better for thinking through bigger issues. - TDD promotes the development of high-quality code

whereas AMDD promotes high-quality communication with your stakeholders and

other developers. - TDD provides concrete evidence that your software works

whereas AMDD supports your team, including stakeholders, in working toward a

common understanding. - TDD “speaks” to programmers whereas AMDD speaks to

business analysts, stakeholders, and data professionals. - TDD is provides very finely grained concrete feedback

on the order of minutes whereas AMDD enables verbal feedback on the order

minutes (concrete feedback requires developers to follow the practice Prove

It With Code and thus becomes dependent on non-AM techniques). - TDD helps to ensure that your design is clean by

focusing on creation of operations that are callable and testable whereas

AMDD provides an opportunity to think through larger design/architectural

issues before you code. - TDD is non-visually oriented whereas AMDD is visually

oriented. - Both techniques are new to traditional developers and

therefore may be threatening to them. - Both techniques support evolutionary development.

Which approach should you take?

The answer depends on your, and your teammates, cognitive preferences.

Some people are primarily “visual thinkers”, also called

spatial thinkers, and they may prefer to think things through via drawing.

Other people are primarily text oriented, non-visual or non-spatial

thinkers, who don’t work well with drawings and therefore they may prefer a TDD

approach. Of course most people

land somewhere in the middle of these two extremes and as a result they prefer

to use each technique when it makes the most sense.

In short,

the answer is to use the two techniques together so as to gain the advantages of

both.

How do you combine the two

approaches? AMDD should be used to

create models with your project stakeholders to help explore their requirements

and then to explore those requirements sufficiently in architectural and design

models (often simple sketches). TDD

should be used as a critical part of your build efforts to ensure that you

develop clean, working code. The

end result is that you will have a high-quality, working system that meets the

actual needs of your project stakeholders.

6. Why TDD?

A significant advantage of TDD is that it enables you to take small steps when writing software. This is a practice that I have promoted for years because it is far more productive

than attempting to code in large steps. For

example, assume you add some new functional code, compile, and test it.

Chances are pretty good that your tests will be broken by defects that

exist in the new code. It is much

easier to find, and then fix, those defects if you’ve written two new lines of

code than two thousand. The implication is that the faster your compiler and

regression test suite, the more attractive it is to proceed in smaller and

smaller steps. I generally prefer

to add a few new lines of functional code, typically less than ten, before I

recompile and rerun my tests.

I think

Bob Martin says it well “The act of writing a unit test

is more an act of design than of verification.

It is also more an act of documentation than of verification.

The act of writing a unit test closes a remarkable number of feedback

loops, the least of which is the one pertaining to verification of function”.

The first reaction that many people have to agile techniques is

that they’re ok for small projects, perhaps involving a handful of people for

several months, but that they wouldn’t work for “real” projects that

are much larger. That’s

simply not true. Beck (2003)

reports working on a Smalltalk system taking a completely test-driven approach

which took 4 years and 40 person years of effort, resulting in 250,000 lines of

functional code and 250,000 lines of test code.

There are 4000 tests running in under 20 minutes, with the full suite

being run several times a day. Although

there are larger systems out there, I’ve personally worked on systems where

several hundred person years of effort were involved, it is clear that TDD works

for good-sized systems.

7. Myths and Misconceptions

There are several common myths and misconceptions which people

have regarding TDD which I would like to clear up if possible. Table 1 lists these myths and describes the reality.

Table 1. Addressing the myths and misconceptions surrounding TDD.

| Myth | Reality |

| You create a 100% regression test suite | Although this sounds like a good goal, and it is, it unfortunately isn’t realistic for several reasons: |

- I may have some reusable

components/frameworks/… which I’ve downloaded or purchased which

do not come with a test suite, nor perhaps even with source code.

Although I can, and often do, create black-box tests which validate

the interface of the component these tests won’t completely validate

the component. - The user interface is really hard to test.

Although user interface testing tools do in fact exist, not everyone

owns them and sometimes they are difficult to use. A common

strategy is to not automate user interface testing but instead to

hope that

user testing efforts cover this important aspect of your system.

Not an ideal approach, but still a common one. - Some developers on the team may not have adequate

testing skills.

Database regression testing is a fairly new concept and not yet

well supported by tools.- I may be working on a

legacy system and may not yet have gotten around to writing the

tests for some of the legacy functionality.

The unit tests form 100% of your design specificationPeople new to agile software development, or

people claiming to be agile

but who really aren’t, or perhaps people who have never been involved

with an actual agile project, will sometimes say this. The reality

is that the unit test form a fair bit of the

design

specification, similarly

acceptance tests form a fair bit of your

requirements specification, but there’s more to it than this.

As Figure 4 indicates, agilists do in fact

model (and

document for that matter), it’s just that we’re very smart about how

we do it. Because you think about the production code before you

write it, you effectively perform detailed design as I highly

suggest reading my

Single Source Information: An Agile Practice for Effective Documentation

article.You only need to unit testFor all but the simplest systems this is completely

false. The agile community is very clear about the need for

a host of

other testing

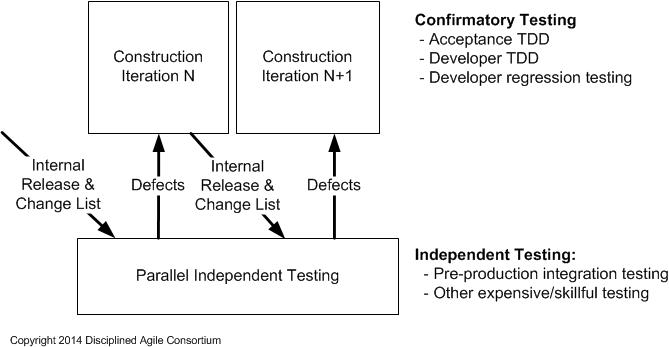

techniques.TDD is sufficient for testingTDD, at the unit/developer test as well as at the

customer test level, is only part of your overall testing efforts.

At best it comprises your confirmatory testing efforts, but as

Figure 5 shows you must also be concerned about

independent testing efforts which go beyond this. See

Agile Testing and Quality Strategies: Reality over Rhetoric for details

about agile testing strategies.TDD doesn’t scaleThis is partly true, although easy to overcome.

TDD scalability issues include:

- Your test suite takes too long to run.

This is a common problem with a equally common solutions.

First, separate your test suite into two or more components. One test

suite contains the tests for the new functionality that you’re

currently working on, the other test suite contains all tests.

You run the first test suite regularly, migrating older tests for

mature portions of your production code to the overall test suite as

appropriate. The overall test suite is run in the background,

often on a separate machine(s), and/or at night. At scale,

I’ve seen several levels of test suite — development sandbox tests

which run in 5 minutes or less, project integration tests which run

in a few hours or less, a test suite that runs in many hours or even

several days that is run less often. On one project I have

seen a test suite that runs for several months (the focus is on

load/stress testing and availability). Second, throw

some hardware at the problem. - Not all developers know how to test.

That’s often true, so get them some appropriate training and get

them pairing with people with unit testing skills. Anybody who

complains about this issue more often than not seems to be looking

for an excuse not to adopt TDD. - Everyone might not be taking a TDD approach.

Taking a TDD approach to development is something that everyone on

the team needs to agree to do. If some people aren’t doing so,

then in order of preference: they either need to start, they need to

be motivated to leave the team, or your team should give up on TDD.

Figure 5. Overview of testing on agile

project teams.

8. Who is Actually Doing This?

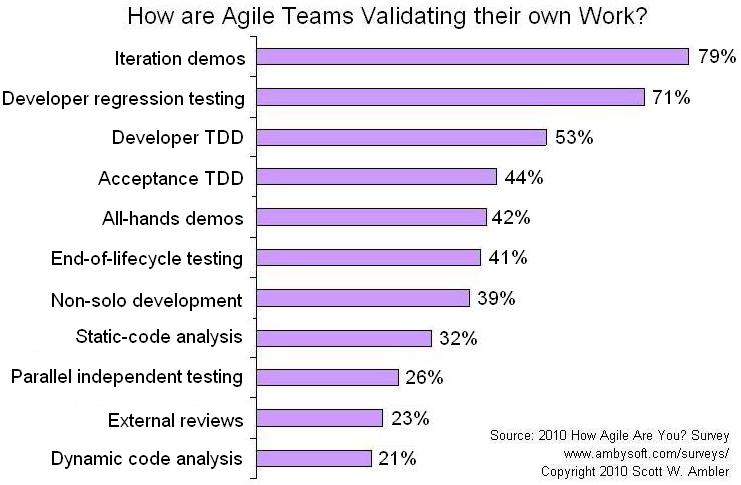

Unfortunately the adoption rate of TDD isn’t as high as I would hope.

Figure 6, which summarizes results from

the

2010 How Agile Are You? survey, provides insight into which validation

strategies are being followed by the teams claiming to be agile. I suspect

that the adoption rates reported for developer TDD and acceptance TDD, 53% and

44% respectively, are much more realistic than those reported in

my

2008 Test Driven Development (TDD) Survey.

Figure 6. How agile teams validate

their own work.

9. Summary

Test-driven development (TDD) is a development technique where you must first write a test that fails before you write new functional code. TDD is being quickly adopted by agile software developers for development of application source code and is even being adopted by Agile DBAs for

database development.

TDD should be seen as complementary to Agile

Model Driven Development (AMDD) approaches and the two can and should be used together. TDD does not replace traditional testing, instead it defines a proven way to ensure effective unit testing. A side effect of TDD is that the resulting tests are working examples for invoking the code, thereby providing a working specification for the code. My experience is that TDD works incredibly well in practice and it is something that all software developers should consider adopting.

10. Tools

List of TDD Tools:

- cpputest

- csUnit (.Net)

- CUnit

- DUnit (Delphi)

- DBFit

- DBUnit

- DocTest (Python)

- Googletest

- HTMLUnit

- HTTPUnit

- JMock

- JUnit

- Moq

- NDbUnit

- NUnit

- OUnit

- PHPUnit

- PyUnit (Python)

- SimpleTest

- TestNG

- TestOoB (Python)

- Test::Unit (Ruby)

- VBUnit

- XTUnit

- xUnit.net

.Net developers may find this comparison of .Net TDD tools interesting.

Books:

Source/s:

1 Comments

Leave a Reply